Many Go developers have previously doubted the performance benefits of sync.Pool. Skeptical questions like “Is it really that fast?” or “Do I need it for small projects?” have been common. However, benchmarks in real-world scenarios clearly demonstrate that sync.Pool is by no means an overrated tool.

Benchmark Setup: Realistic Workloads

This analysis was performed under the following conditions:

- Allocation Method: Slice-based buffers (most common in Go)

- Batch Size: 1,000 objects allocated and returned per iteration

- Allocation Size: 32 bytes to 131,072 bytes (7 stages)

- Concurrency: GOMAXPROCS=1 (single-threaded) vs GOMAXPROCS=8 (8 P parallel processing)

Crucially, buffers were stored in reusable slices to reflect the cache efficiency of pools in actual applications.

Key Findings: Performance Discrepancy by Size

1. Significant Improvement Even in Single-Threaded (GOMAXPROCS=1) Environments

| Allocation Size | Make(ns/op) | SyncPool(ns/op) | Improvement Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32B | 19,436 | 17,941 | 1.1x |

| 256B | 35,893 | 18,078 | 2.0x |

| 1KB | 108,946 | 18,095 | 6.0x |

| 4KB | 402,517 | 18,464 | 21.8x |

| 16KB | 1,984,701 | 18,657 | 106.4x |

| 64KB | 6,562,374 | 18,677 | 351.4x |

| 128KB | 11,345,907 | 18,156 | 624.9x |

Even in a single-threaded environment, a substantial performance difference emerges for medium to large buffers. Especially for sizes 16KB and above, a difference of over 100 times is observed. This is because direct allocation (Make) involves complex operations such as memory clearing (zeroing), GC tracking, and page allocation.

2. Dramatic Improvement in Parallel Environments (GOMAXPROCS=8)

The true value of sync.Pool shines in parallel processing environments:

| Allocation Size | Make(ns/op) | SyncPool(ns/op) | Improvement Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32B | 18,687 | 4,261 | 4.4x |

| 256B | 72,857 | 8,535 | 8.5x |

| 1KB | 181,995 | 8,967 | 20.3x |

| 4KB | 599,625 | 9,499 | 63.1x |

| 16KB | 1,725,698 | 3,899 | 442.6x |

| 64KB | 4,657,615 | 3,816 | 1,220.5x |

| 128KB | 8,826,957 | 4,482 | 1,969.4x |

With GOMAXPROCS=8, performance improvements of up to 2,000 times were recorded for large object allocations. This is due to GC assist and lock contention experienced by the Make method as all goroutines compete for memory allocation.

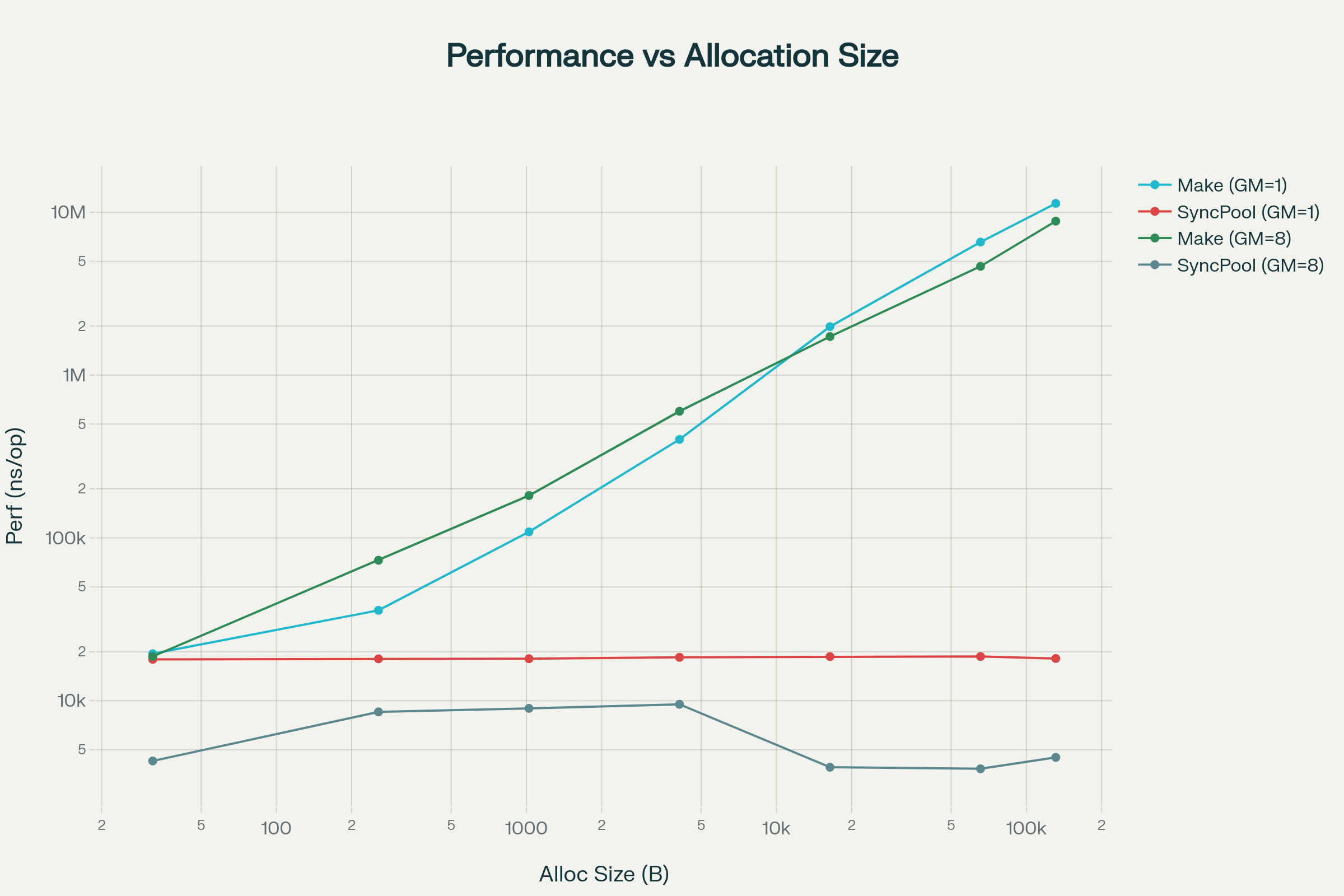

Performance Gap Visualized with Charts

Absolute Performance Comparison (log scale, lower is faster):

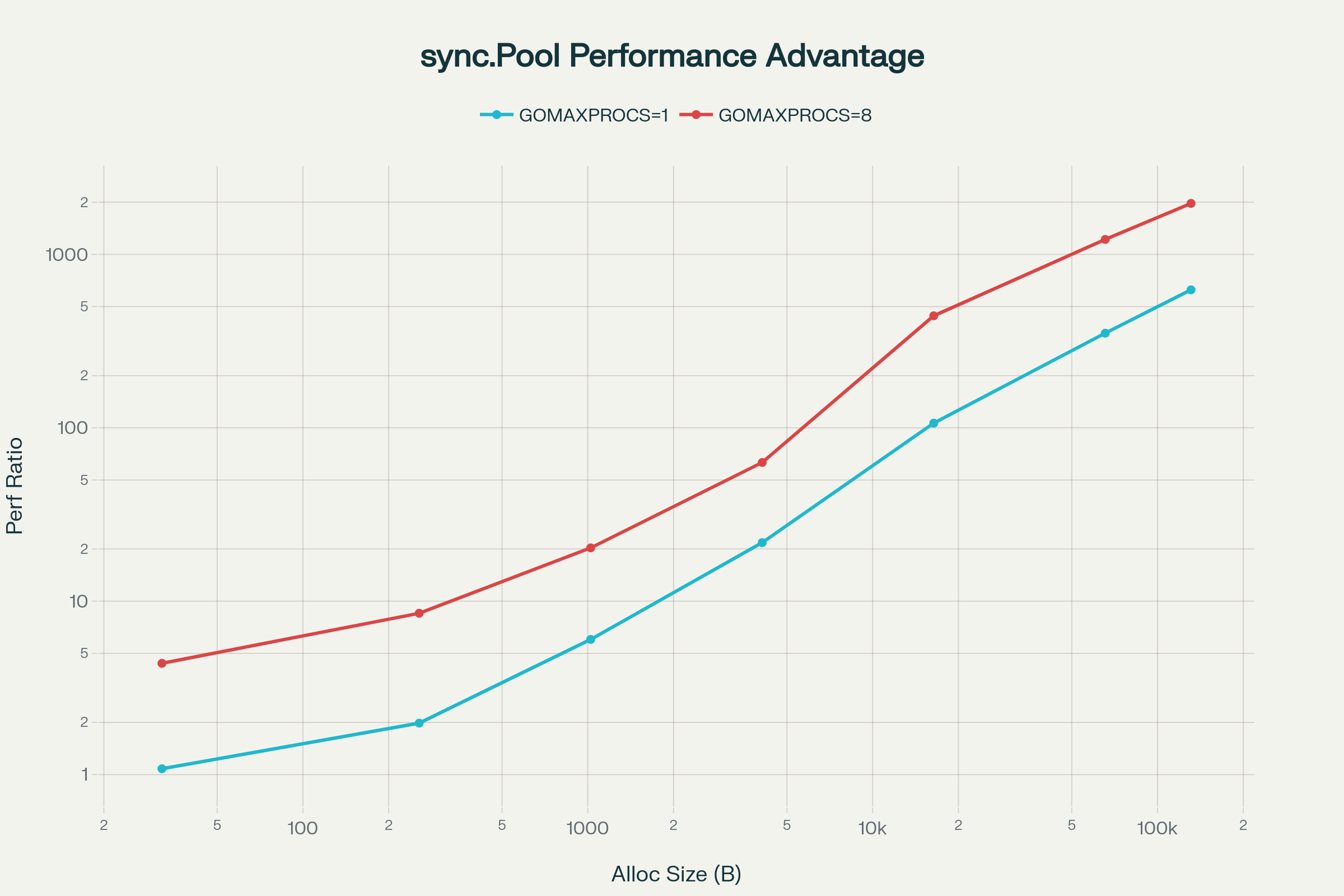

Performance Improvement Ratio (log scale):

As seen in the charts, the improvement rate increases non-linearly with size. In GOMAXPROCS=8, the difference becomes even more drastic, illustrating how severe GC and memory allocation contention can be in multi-core environments. While sync.Pool’s performance remains almost constant regardless of size (~18μs), Make slows down exponentially with increasing size.

Log-scale charts more clearly visualize the gap between the two approaches. The vertical distance between the Make and SyncPool lines dramatically widens at larger allocation sizes.

Why This Difference?

Cost Structure of Make

Direct allocation (make([]byte, size)) goes through the following steps:

Memory page allocation (size-based cost), full memory clearing (zeroing), GC metadata updates, inclusion in the GC tracking system, and in parallel environments, GC assist triggers and global lock contention.

The larger the size, the more linearly the amount of clearing work increases, the greater the GC pressure, increasing the probability of GC assist (potentially pausing all goroutines), and allocation lock contention occurs in multi-core environments.

Efficiency of sync.Pool

pool.Get() performs a check of the local P-specific storage (very fast, no locks) and returns an already cleared object.

pool.Put(obj) directly stores the object in the local P storage (no locks), making it available for reuse in the next Get.

The advantages of sync.Pool include lock-free per-P storage, no need for memory clearing (objects are already clean), outside of GC tracking (discarded only after generational cleanup), and size-independent performance (only pointer get/put).

Practical Implications: When is it Important?

When sync.Pool is Essential

WebSocket/Network Servers: High GC pressure due to allocating several KB buffers per request → 100-500x improvement (higher with more GOMAXPROCS)

Message Queue Systems: Concurrent processing of tens of thousands of messages → 1,000x+ improvement (for 64KB+ messages)

High-Performance Data Processing: Frequent use of temporary buffers during batch processing → 200-600x improvement

Real-time Game Servers: Hundreds of allocations per game tick → 500x+ improvement (cumulative effect)

Conversely, When sync.Pool is Unnecessary

Very Small Objects (< 32 bytes): 1-2x improvement, overhead might be greater

Low Allocation Frequency: Less than a few dozen allocations per second

Single Goroutine + Small Buffers: 1-2x improvement is not significant

Actual Application Strategy

1. Measure First

Always verify with benchmarks before production deployment. Consider the actual size of target objects, allocation patterns, and parallelism to confirm if sync.Pool adoption is justified.

2. Size-Based Selection

For small objects (< 256B), direct allocation might be better due to higher pool overhead. For medium sizes (256B ~ 16KB), pool usage is recommended (4-22x improvement), and for large objects (> 16KB), a pool is essential (100-2000x improvement).

3. Verify with Profiling

After benchmarking, confirm if memory allocation is a bottleneck with actual profiling. Track allocation counts and memory usage with go test -benchmem -bench=. ..

Conclusion

sync.Pool is not an overrated tool, but rather an underrated one.

The benchmark results are clear:

✅ 4KB or more: Definitely use sync.Pool (at least 20-100x improvement)

✅ 16KB or more: Performance is critical (100-2,000x improvement)

✅ Parallel Environments: sync.Pool usage is almost essential (2-10x increase in improvement rate)

⚠️ Small Objects: Judge after profiling (potential overhead)

⚠️ Single Thread: Relatively lower improvement rate (but still effective)

Most modern Go backend systems run in multi-core parallel environments. In such environments, sync.Pool is not just a performance optimization but an essential architectural pattern.

The next time you deal with temporary memory in your project, consider sync.Pool first. The numbers in these charts sufficiently prove its value.

Benchmark Code

package makevssyncpool

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"testing"

)

func BenchmarkAllocations(b *testing.B) {

// Define various allocation sizes.

allocSizes := []int{32, 256, 1024, 4096, 16384, 65536, 131072}

numAllocsLevels := []int{100, 1000} // Number of objects to allocate at once.

for _, numAllocs := range numAllocsLevels {

b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("NumAllocs_%d", numAllocs), func(b *testing.B) {

// --- Warm-up before starting benchmarks ---

// Pre-activate the pool for the largest size (131072) to reduce benchmark distortion.

b.Logf("Warming up the pool with size 131072 for numAllocs %d...", numAllocs)

warmupPool := sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} {

buf := make([]byte, 131072)

return &buf

},

}

warmupBufs := make([]*[]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

warmupBufs[i] = warmupPool.Get().(*[]byte)

}

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

warmupPool.Put(warmupBufs[i])

}

// --- Byte Slice Benchmarks ---

b.Run("Slice", func(b *testing.B) {

// 1. Performance measurement using make([]byte, size)

b.Run("Make", func(b *testing.B) {

for _, size := range allocSizes {

b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("Size_%d", size), func(b *testing.B) {

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

// Prevent compiler optimization by storing the result in a slice.

s := make([][]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = make([]byte, size)

}

}

})

})

}

})

// 2. Performance measurement using sync.Pool (*[]byte)

b.Run("SyncPool", func(b *testing.B) {

for _, size := range allocSizes {

b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("Size_%d", size), func(b *testing.B) {

pool := sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} {

buf := make([]byte, size)

return &buf

},

}

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

// Create a buffer slice for Get/Put only once.

bufs := make([]*[]byte, numAllocs)

for pb.Next() {

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

bufs[i] = pool.Get().(*[]byte)

}

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

pool.Put(bufs[i])

}

}

})

})

}

})

})

// --- Byte Array Benchmarks ---

b.Run("Array", func(b *testing.B) {

// 1. Performance measurement using new([N]byte)

b.Run("New", func(b *testing.B) {

for _, size := range allocSizes {

b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("Size_%d", size), func(b *testing.B) {

switch size {

case 32:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

// Prevent compiler optimization by storing the result in a slice.

s := make([]*[32]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([32]byte)

}

}

})

case 256:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[256]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([256]byte)

}

}

})

case 1024:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[1024]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([1024]byte)

}

}

})

case 4096:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[4096]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([4096]byte)

}

}

})

case 16384:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[16384]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([16384]byte)

}

}

})

case 65536:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[65536]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([65536]byte)

}

}

})

case 131072:

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

for pb.Next() {

s := make([]*[131072]byte, numAllocs)

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

s[i] = new([131072]byte)

}

}

})

}

})

}

})

// 2. Performance measurement using sync.Pool (*[N]byte)

b.Run("SyncPool", func(b *testing.B) {

for _, size := range allocSizes {

b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("Size_%d", size), func(b *testing.B) {

switch size {

case 32:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([32]byte) }})

case 256:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([256]byte) }})

case 1024:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([1024]byte) }})

case 4096:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([4096]byte) }})

case 16384:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([16384]byte) }})

case 65536:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([65536]byte) }})

case 131072:

runArrayPoolBenchmark(b, numAllocs, sync.Pool{New: func() interface{} { return new([131072]byte) }})

}

})

}

})

})

})

}

}

func runArrayPoolBenchmark(b *testing.B, numAllocs int, pool sync.Pool) {

b.RunParallel(func(pb *testing.PB) {

// Create a buffer slice for Get/Put only once.

bufs := make([]interface{}, numAllocs)

for pb.Next() {

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

bufs[i] = pool.Get()

}

for i := 0; i < numAllocs; i++ {

pool.Put(bufs[i])

}

}

})

}